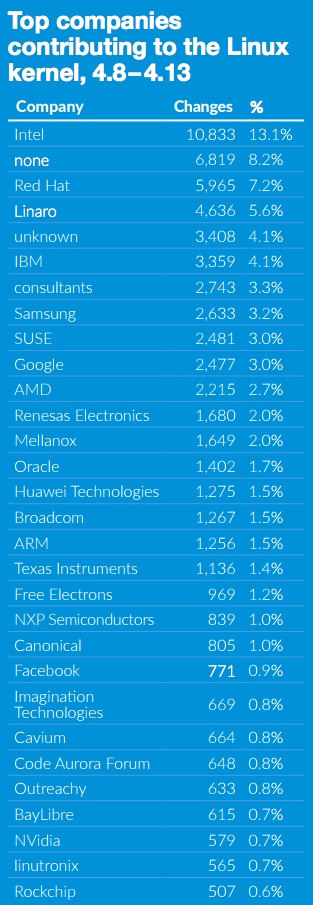

There should be no internal boundaries within the project. But, although any company can improve the kernel for its specific needs, no company can drive development in directions that hurt the others or restrict what the kernel can do. The majority of developers are paid for their work-and the changes they make serve the companies they work for. Some 5,062 individual developers representing nearly 500 corporations have contributed to the Linux kernel since the 3.18 release in December of 2014. Corporate participation in the process is crucial, but no single company dominates kernel development. The rule gives users assurance that upgrades will not break their systems as a result, they are willing to follow the kernel as it develops new capabilities. If the community finds out that a change caused a regression, they work very quickly to address the issue. Over a decade ago the kernel developer community made the promise that if a given kernel works in a specific setting, all subsequent kernels will work there, too. The kernel's strong "no regressions" rule is also important. As a result, we have a single codebase that scales from tiny systems to supercomputers and that is suitable for a huge range of uses.

No particular user community is able to make changes at the expense of other groups. But it also ensures that the kernel remains suited to a wide ranges of users and problems.

#LINUX KERNEL DEVELOPMENT CODE#

This can be intensely frustrating to developers who find code they have put months into blocked on the mailing list. The kernel's strongly consensus-oriented model is important.Īs a general rule, a proposed change will not be merged if a respected developer is opposed to it. Without the right tools, a project like the kernel would simply be unable to function without collapsing under its own weight. Kernel development struggled to scale until the advent of the BitKeeper source-code management system changed the community's practices nearly overnight the switch to Git brought about another leap forward. Spreading out the responsibility for code review and integration across many hundreds of maintainers gives the project the resources to cope with tens of thousands of changes per release, without sacrificing review or quality.

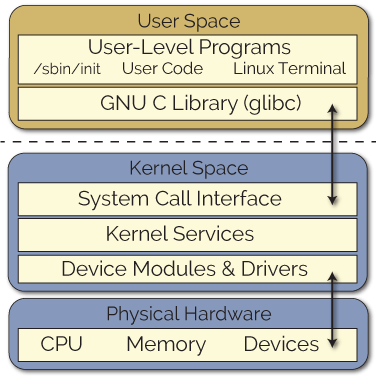

#LINUX KERNEL DEVELOPMENT DRIVER#

Examples of this is networking, wireless, different driver subsystems like PCI or USB, or different individual filesystems like ext2 or vfat. Very early the idea of maintainers of different areas of the kernel came about, where the responsibility of a portion of the kernel was assigned to an individual familiar with that area. Process scalability requires a distributed, hierarchical development model.Ī long time ago, all changes went directly to Linus Torvalds, but that quickly proved unwieldy as no one single person can keep up with a project as diverse as an operating system kernel.

And developers know that if they miss one release cycle, there will be another one in two months, so there is little incentive to try to merge code prematurely. Integrating new code on a nearly constant basis makes it possible to bring in even fundamental changes with minimal disruption. New code is quickly made available in a stable release. Short cycles address all of these problems. But, more importantly, such long cycles meant that huge amounts of code had to be integrated at once, and that there was a great deal of pressure to get code into the next release, even if it wasn't ready. That meant considerable delays in getting new features to users, which was frustrating to users and distributors alike. In the early days of the Linux project, a new major kernel release only came once every few years. It may be many years before we fully understand the keys to the Linux kernel's success, but there are a few lessons that stand out even now. Over time, this evolution has created a resiliency that has allowed the project to go from one strength to the next while avoiding the forks that have split the resources of competing projects. We make new tools, like Git, and constantly change how we work together. And then we make changes that improve the process. Developers can openly and honestly discuss how they interact with each other and how the development process works. Now every year kernel developers make a point to gather in person to work out technical issues and, crucially, to review what we did right and what we did wrong over the past year.

#LINUX KERNEL DEVELOPMENT FREE#

Free online course: RHEL Technical OverviewĪbout 16 years ago, most of the kernel developers had never met each other in person-we'd only ever interacted over email-and so Ted T'so came up with the idea of a Kernel Summit.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)